Preface and Prelude

My Walk on the Moon – Peace Corps Côte d’Ivoire 1969-71

Preface

Why wait more than 50 years to put down my recollections of Peace Corps service? The imprint Peace Corps left on my being is indelible. It was a formative experience that brought the very essence of my purpose, potentials, and values into focus. In fact, I do not see any separation between my Peace Corps service and the rest of my life after ending service in May 1971. My enduring choices, service and relationships were strengthened by my Peace Corps service, and continue unbroken. So in effect, my Peace Corps experience is still going strong.

The stories that follow are not chronological. Rather they follow themes, perennial lessons planted in fertile soil, life lessons and insights that have nourished me. I have but few documents and no letters remaining from my time in the Peace Corps, nor of the training that preceded it. However, that time remains well rooted in my memory and is a part of me.

I am very much a child of the John F. Kennedy generation, entering my teens with his challenge to “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Then, a few years later crying in anguish and disbelief in the halls of high school upon hearing the news of his assassination.

When Kennedy established the Peace Corps on March 1, 1961, it was what the soul of our generation was waiting for. There was no question in my mind that it would become a part of my life journey.

My Peace Corps service coincided with NASA’s Apollo missions preparing to eventually make a moon landing. On July 20, 1969, another goal of John F. Kennedy was accomplished on the Apollo 11 mission, when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed their Apollo Lunar Module and walked on the surface of the moon.

In my mind, “landing” and “walking” in an Iron Age communal agrarian village had so many more dimensions and impact on the U.S. and on our host country than did Neil Armstrong’s walk on the moon!

Prelude

“Do you want to participate in Dr. King’s Poor Peoples’ Campaign in Washington, D.C.?” was the greeting I got from Earl Avery, head of student activities at UCLA, when I returned from spring break working in Tijuana, Baja California. It was late March 1968, just before the beginning of the spring quarter.

I was heading for the office of UCLAmigos in Kerckhoff Hall, my “base camp” where I organized work projects in the barrios of Tijuana for students during school breaks. UCLAmigos was fashioned after work camps in post World War II Europe where young people from many countries would spend their holidays rebuilding. The current Amigos project was building la Escuela para Sordos Mudos, a school for deaf-mute children in Tijuana.

After only a moment’s hesitation I said, “Yes!” A frantic few days followed, convincing some professors to sponsor me for independent study credits, putting official and personal affairs in order, and preparing for my trip. A few days later I arrived at Stanford University with four of my fellow students for training in non-violent action, and a multifaceted tutorial on what to expect, and our role at the Poor People’s Campaign. I was staying in a house that also served as a safe house on the underground for AWOL soldiers who were heading to Canada instead of Vietnam, additional training I hadn’t planned on.

After only a moment’s hesitation I said, “Yes!” A frantic few days followed, convincing some professors to sponsor me for independent study credits, putting official and personal affairs in order, and preparing for my trip. A few days later I arrived at Stanford University with four of my fellow students for training in non-violent action, and a multifaceted tutorial on what to expect, and our role at the Poor People’s Campaign. I was staying in a house that also served as a safe house on the underground for AWOL soldiers who were heading to Canada instead of Vietnam, additional training I hadn’t planned on.

On April 4 Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. That afternoon we spent organizing vigils and protests at Stanford. Several universities withdrew their students from participating in the Campaign because D.C. had erupted in violent grief and anger, the inner city torn apart and smoldering. Questions arose about the leadership of the Campaign, its cohesiveness, and the mood of Congress, adding to the uncertainty. The UCLA Dean of Students, Charles Young, left the choice to go or not to go up to us, and we all opted to go to D.C.

On April 4 Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. That afternoon we spent organizing vigils and protests at Stanford. Several universities withdrew their students from participating in the Campaign because D.C. had erupted in violent grief and anger, the inner city torn apart and smoldering. Questions arose about the leadership of the Campaign, its cohesiveness, and the mood of Congress, adding to the uncertainty. The UCLA Dean of Students, Charles Young, left the choice to go or not to go up to us, and we all opted to go to D.C.

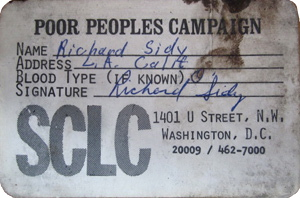

Just days after Dr. King’s death, I arrived in Washington DC in the midst of an urban riot to work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King’s organization, at the office at 14th and U streets in the heart of the inner city. Once there I worked to prepare for the arrival of poor peoples’ caravans from all over the United States. I helped build, and then lived in Resurrection City on the National Mall at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial during the whole campaign. My daily contact and participation with leaders and people in this movement to raise political awareness of poverty in America, was an awakening.

Besides political action, lobbying, education, and civil disobedience, Resurrection City had a vibrant cultural and spiritual impact where mayor Jesse Jackson in dashiki and Afro summoned our “Soul Force” each morning. We marched and lived with veterans of the Civil Rights movement, now leaders of the Campaign, and with a community of diverse groups of poor people from babes to elders – urban, rural, African American, Chicano, Appalachian, and Native American, people from all corners of our nation. The stories and songs of their lives and aspirations documented their traditions, neglect, struggles, faith, and strength.

There was music, revival meetings, soul food in a tent, and incessant rain and mud. When the rain stopped, we could sit by the reflecting pool and talk with eminent visitors like Alex Haley who told us the story of his book “Roots” that he was working on. We had concerts and impromptu jam sessions – Pete Seeger, Reverend Kirkpatrick, a host of freedom songs; performers including Muddy Waters, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, C. L. Franklin, Dizzy Gillespie, Harry Belafonte, James Moody, Sammy Davis Jr., and Jimmy Collier. Adding education to activism, teachers and leaders from the civil rights movement, from universities, and from southern churches to urban community centers, held workshops in tents or in the open as part of the “Freedom School.”

On June 8 we stood respectfully along the road as the funeral cortege of Robert F. Kennedy wound its way around the Lincoln Memorial to his burial site in Arlington Cemetery, three days after his assassination.

I returned to UCLA in late June just before the National Guard had cleared Resurrection City, in order to attend the summer quarter to complete my requirements for graduation, postponed by my involvement in Poor People’s Campaign.

My invitation to join the Peace Corps Dominican Republic arrived a few days later. I had to decline the invitation, but replied that I would be available in August. I received another invitation for Rural Housing Animator, in the Ivory Coast, West Africa, and I was ready!

If 1967 was “the Summer of Love,” summer 1968 was the summer of violence, smashed hopes and radicalization on both the left and the right. The anti-war protests morphed into the Chicago police riot at the Democratic Convention. Leaders of the Black Power movement told us at the Poor People’s Campaign that it was the last chance for non-violence. George Wallace embodied an emboldened reaction to the civil rights movement, and became a presidential candidate appealing to those unhappy with the commitment by the Democratic Party to desegregation. Riding the southern backlash to the civil rights movement, Wallace ran for president under the banner of the American Independent Party.

This agonizing cultural and political divide was intensified by the presidential campaigns of the major parties in 1968. It represented the “backlash” politics of crime and race, an unpopular war, and divided political parties. On the Democratic side the tension ignited between the anti-war message and activism of Eugene McCarthy and his youthful followers, the killing of Robert Kennedy, and the establishment candidacy of Hubert Humphrey carrying on policies of Lyndon B. Johnson. On the Republican side, candidate Richard Nixon emerged as a “centrist” between the liberals George Romney and Nelson Rockefeller and conservative Ronald Reagan.

This was the backdrop when I received my assignment to serve in the Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast). After accepting my assignment, I received my invitation to Peace Corps orientation in Philadelphia to get ready for training and to prepare for my country of service. The orientation, medical and dental exams, and paperwork were scheduled to start on Wednesday, November 6. The day after the presidential election!

Many new volunteers, representing a variety of programs to countries all over the world, gathered in Philadelphia. We were both somber and electric with anticipation. Many showed up still wearing their “McCarthy for President” buttons, but our new president was Richard M. Nixon, and the Peace Corps would now be under the direction of his administration. What a time to be leaving to serve abroad in the Peace Corps armed with our idealism instead of with weapons of death and destruction!

After a few days of orientation, interviews, and check-ups, we all were sent on our way to training centers in various places. The Côte d’Ivoire trainees went to the St. Croix, Virgin Islands Training Center with several other groups destined for West Africa – Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) and Liberia. We were Rural Housing Animators, while others were health workers, school garden instructors, and teachers. We would have language and cultural instruction, technical training, and tests of our adaptability and resolve.

On January 28, 1969 our group boarded a flight from New York City to Paris, the first leg of our trip to the Côte d’Ivoire. The plane was filled with new Peace Corps Volunteers who, having finished their three months of training, were on their way to assignment. Paris would be the hub from which all would be dispersed on a multitude of assignments in a variety of countries and cultures. On boarding the plane in New York I was surprised to see my best friend from UCLA, Paul Bundick, who was on his way to assignment to Uttar Pradesh in India. While he was learning Hindi and well digging, I had been learning the French and Dyula languages, and techniques of rural Ivoirian construction. Our friendship would provide the basis for a cultural fusion when our paths finally came together again in Los Angeles almost three years later.

Feeling Naked

The dirt road approaching the falls had huge, ancient mango trees on both sides forming a lush, shaded passageway to the pool. The pool was beautiful, a deep swimming hole in a smooth sculpted stone basin, clear and calm. There were no other people there. At one end of the pool a waterfall, “les Cascades de Banfora,” splashed down from a rocky cliff. I didn’t waste any time getting my dusty clothes off and going for a swim. The water washed away all my tiredness of that day’s trip along with the red dust caked in all my pores, and I felt renewed. (Read more >>)