Initiation

Finding Where I Fit in the Village

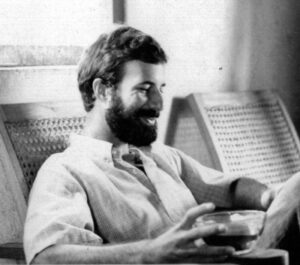

“Your beard is bad,” the wizened old chief said. “Why is it bad?” I asked. “Beards are for old men,” he replied, “and you are not old.” “In my country the young men have beards, and the old men do not,” I said. This was the end of the 1960’s and of course beards on young people were a cultural and political statement. In the village, too, beards were cultural and political statements. Elder men wore beards indicating their esteemed position in life and their authority.

“Your beard is bad,” the wizened old chief said. “Why is it bad?” I asked. “Beards are for old men,” he replied, “and you are not old.” “In my country the young men have beards, and the old men do not,” I said. This was the end of the 1960’s and of course beards on young people were a cultural and political statement. In the village, too, beards were cultural and political statements. Elder men wore beards indicating their esteemed position in life and their authority.

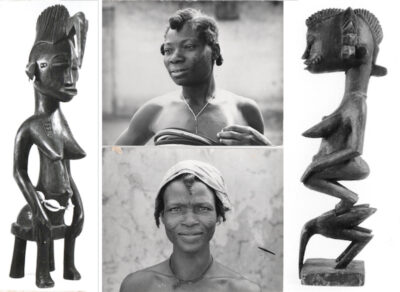

In Senufo society, hair played an important symbolic role indicating one’s place in the life cycle, one’s rights, and responsibilities. It was an age-graded society, where people were very conscious of their place in the life continuum. Relationships were based on generational names indicating age, like when I was called either “older” or “younger” brother. This placement made clear who had authority over whom.

Besides authority, hairstyle indicated social role. The Senufo observed a seven-year cycle. Every seven years a person passed to the next stage of life with different knowledge, rights and duties often marked by change of hairstyle.

This was even more important for females. For women, the most significant hairstyle came when they were of childbearing age. At that time their hair was braided to represent a bird nesting upon the head. This was an icon of fertility and represented conception, union of the bird (spirit) and the woman. These images prevailed in the Madonna-like statues that the Senufo carved, and on many masks. After childbearing age women shaved their heads.

This was even more important for females. For women, the most significant hairstyle came when they were of childbearing age. At that time their hair was braided to represent a bird nesting upon the head. This was an icon of fertility and represented conception, union of the bird (spirit) and the woman. These images prevailed in the Madonna-like statues that the Senufo carved, and on many masks. After childbearing age women shaved their heads.

For men, the most significant hair was the beard, when men became elders. In general, people kept their hair close cropped or heads shaved. Once we were visited by an African American student who was traveling in the Côte d’Ivoire, and had been told that a couple of Peace Corps volunteers were living in Sirasso, a traditional village in the north, and that he should visit on his travels. He had a large Afro hairstyle popular in the US at the time, and the people in the village were afraid of him. They thought he was a crazy man, since only crazy people had such hair.

For men, the most significant hair was the beard, when men became elders. In general, people kept their hair close cropped or heads shaved. Once we were visited by an African American student who was traveling in the Côte d’Ivoire, and had been told that a couple of Peace Corps volunteers were living in Sirasso, a traditional village in the north, and that he should visit on his travels. He had a large Afro hairstyle popular in the US at the time, and the people in the village were afraid of him. They thought he was a crazy man, since only crazy people had such hair.

My partner and I were in our early twenties, but in some ways we had the authority of elders, since we had responsibilities of functionaries and were representing both an Ivoirian ministry and the USA. This was an obstacle that was confusing in terms of where to place us, how to relate to us, and where we fit in.

One night towards the end of our first year we heard drumming and singing coming from the sacred grove of ancient trees at the edge of the village. The next afternoon a group of young men with talking drums, and ceremonial flute whistles came to our house. They were with their families singing and chanting with great energy and joy. They moved through the village stopping at each family compound in celebration.

We found out that we were witnessing an event that only happens every seven years – the graduation of men from the Poro, or men’s initiation society. Their cohort had completed their fourth seven-year initiation cycle, attaining the age of 28. They would officially now take their place as men of authority and privilege in the Village.

Starting at age 21, or the third cycle of life, they had entered the Poro for seven years. For the first thirty days they lived in the sacred grove isolated from the village. During their term of initiation they would learn the secrets of Senufo spiritual life, make all sorts of crafts and tools, do community service projects, and be the masked dancers at celebrations, ceremonies, and funerals. A chief could convoke them to cultivate a large plantation, and in the event of threat they would be the soldiers and protectors of the village.

days they lived in the sacred grove isolated from the village. During their term of initiation they would learn the secrets of Senufo spiritual life, make all sorts of crafts and tools, do community service projects, and be the masked dancers at celebrations, ceremonies, and funerals. A chief could convoke them to cultivate a large plantation, and in the event of threat they would be the soldiers and protectors of the village.

As the new group of initiates entered the sacred grove, we were starting a new project. We had designed an improved and permanent marketplace that could withstand heavy wind and rain in the monsoon season, and provide shaded places for merchants. We decided with the village chiefs that this would be the first service project for the new initiates. I told them that our Peace Corps service was like our initiation, it would teach us many skills benefiting our communities, and test our character.

That was a major turning point for our time in Sirasso in terms of our relationship with the traditional village structure. Finally, the elders and chiefs knew where we fit. We were the same age as the new initiates and they treated us as such. The initiates were our peers and we were all doing our service. Each age group had its chiefs, and the Poro was a training ground for future leaders. The elders also made us chiefs of the new Poro group and while the new initiates were not allowed to enter the village nor talk to anyone during the first thirty days, our house and building site became accepted places for them.

Everything came together in the minds of the villagers, of us, and of our peers. Suddenly we all knew our place in their society, and we all embraced it. We had found our age group. The elders and chiefs started relating to us differently. They started ordering us around and no longer hesitated in being more open and frank with us. They freely expressed their needs and grievances, and we became advocates for them with the local government.

For almost a year, our group of initiates worked on the market with our two masons and a carpenter. We were a strong workforce of young men at our prime, building for the community. Our fellow initiates learned how to use a construction level, measuring tape. and other construction tools. They laid out foundations, tied reinforcing steel, built forms, mixed and poured concrete, built trusses, and did roofing. They dug footings, made and laid block, excavated sand and hauled water.

Our house became an annex of the sacred grove, a gathering place for many of our fellow initiates. Sometimes they would come with traditional instruments, balaphones, koras and drums, and my partner Bill would join in on his guitar. Our work group had become a social group, and the experience of working together as equals solidified our friendship.

When the market was finished it was a work we all took pride in. Our team had learned many skills, and the village had gained a market that would grow and stimulate trade. It was a small step of modernization based on a traditional need, and built within the traditional social and cultural structure.

When the market was finished it was a work we all took pride in. Our team had learned many skills, and the village had gained a market that would grow and stimulate trade. It was a small step of modernization based on a traditional need, and built within the traditional social and cultural structure.

For me, this project unfolded another dimension of service. I understood something central to becoming an adult within a community. There is something universal and essential to the process of initiation, of the right of passage into a new stage of life involving ceremony and work that develops new rights, knowledge, and responsibilities.

Drawing Water

It was in the midst of the dry season when we arrived in Sirasso, February 1969. Crammed in the front seat of a Peugeot 404 pick-up truck with Monsieur Despond at the wheel, corpulent and sweating profusely, for a whole parched day of swirling red dust on washboard road, we finally made it to our site. Despond was a French civil servant with the Ministry of Construction and Urbanism. He was a remnant of colonial rule, about to finally leave the Côte d’Ivoire in the hands of Ivorians. He duly delivered us to our new home. (Read more >>)