An ni bara

In Praise of Work

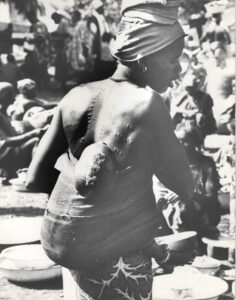

“An ni bara” she said to me in Dyula without breaking her stride. A load of firewood was on her head; a baby was held to her back by a length of cloth tucked around her breasts; her bare feet moved over the gravel trail as she hastened back from the fields. She moved at a brisk and rhythmic pace, walking stick in hand, having covered several kilometers after a day’s work. “M’ba, an ni bara,” I replied.

“An ni bara” literally means “We and work.” It is the greeting spoken as you meet someone who is working. However, in an environment where survival depends on work, and the work is hard, “an ni bara” means so much more. It means, “I see that you are working,” “Thank you for your work,” “Take heart and keep going,” “You are doing a great job,” “In work we are strong.” This greeting is spoken, almost chanted like a mantra, praise and encouragement, a call with response like in gospel music, that joins our hearts.

When I was greeted with “an ni bara” by a woman in our village returning loaded down from the fields, it was the highest compliment and recognition I could have ever received. Greetings in West Africa build community; they are elaborate and almost like rhythmic singing in a ceremonial way. “An ni bara” stands alone, apart from the ceremony of first greeting, it is more like what today we would call a “shout out” when you come up to someone who is doing something “awesome.”

When I was greeted with “an ni bara” by a woman in our village returning loaded down from the fields, it was the highest compliment and recognition I could have ever received. Greetings in West Africa build community; they are elaborate and almost like rhythmic singing in a ceremonial way. “An ni bara” stands alone, apart from the ceremony of first greeting, it is more like what today we would call a “shout out” when you come up to someone who is doing something “awesome.”

The Senufo with whom I lived had a reputation among other tribes of being hard workers and philosophers. They had a power recognized far and wide. They were adept at farming, growing surpluses of staple crops, such as rice, corn, millet, peanuts, igname (yam/cassava), and quantities of other crops such as okra, manioc, tomatoes, African eggplant, and mangos. These were all cultivated in communal plantations at a distance from the village. For generations their farming was all done by hand, their crops only watered by monsoon rains.

So what was I doing to merit such a greeting? I was next to my house digging in the dirt with the goal of planting a garden. This did not really have anything to do with my Peace Corps assignment, and I was a total novice at gardening. The only reason I can think of is that someone must have sent me some seeds from home, and I felt obliged to plant them.

There was a very good reason that no one had a garden in the village. Sheep, goats, guinea hens, chickens, and pigs all roamed freely through village streets, paths and courtyards. They kept everything clean, since most of the waste was plant based, and they ate it up. To have a garden it would have had to be walled in – a construction project as well as a garden. My prospective plot was wide open, the dirt devoid of organic matter, and no water source for irrigation to get the alien seeds started. I didn’t even have proper tools except for a shovel borrowed from our construction site. Ultimately, my attempt at a garden was a total failure.

The greeting I got from a village sister was an expression of empathy. It was her acknowledgement of me working in the heat and dirt, and of my effort to do what my hosts did on a daily basis for survival. But the real lesson for me was that I realized that I did not have the ability to survive in that environment – no valued skills to contribute to their basic subsistence. It was a moment of truth, showing me what was needed to be self-sufficient, and able to survive without markets, industry and other people providing my food, shelter, water, energy, technology, and clothing.

Not only was I a graduate of one of the top ten universities in the leading industrialized country, but also many of my peers in the 60’s had dropped out of that culture to seek a communal self-sufficient way on life. I was not living on a hippy commune, however, but I was experiencing a way of life not only effectively surviving, but also based on a rich culture and traditions. I was essentially witnessing the utopia envisioned by many of my peers in the U.S.

Even with my educational background I was unfit for survival in rural Cote d’Ivoire. Traditional Senufo culture was fully sustainable if left alone, but I was there to be a change maker. If manufactured goods had not started coming to the village via markets, if the young government of the Côte d’Ivoire had not made it a priority to develop the outlying regions in the bush to have a government presence, we wouldn’t have seen the growth of new material goals, a window upon a world in which manufactured goods and money ruled, nor the desire for “modernization.” I realized that my role would be to help the people I was living with transition from the Iron Age to the 20th Century. They would skip the industrial revolution, while taking advantage of many of its creations.

The words “sustainable development” were not in our vocabulary yet, but we did have the concept of “appropriate technology.” In our village we had no electricity, no telephones, no running water. Using the sun to generate electricity or to cook was not an option. We would be part of a transition based on development paradigms of Colonial and post World War II “third world” methods and goals. How could I help these newly independent Ivoirians avoid the mistakes of materialism, pollution and degradation of ecosystems and still develop? I was torn, since I came from a culture that was learning about the environmental crises produced by increased industrialization and consumerism. We were on the verge of the first “Earth Day” in the U.S., and my peers were trying to reverse many of the negative effects of the modern age.

I was fortunate to live and work in a traditional Senufo village where the majority of the inhabitants were animists, and there was a robust craft tradition providing many of the necessities and adornments of daily life and celebration. Textile weaving and dying, forging steel tools, bronze casting, making ceramic cookware, wood-working and carving, basketry, adobe and thatch construction, and cultivating the earth with conscious awareness of sustainable agriculture and gratitude for the fruits of community labor, were all part of the way of life that I discovered. Without romanticizing a “primitive” way of life, I still was able to get a glimpse into a working society where handcrafts flourished within an integrated spiritual and economic framework based upon the relationship between human needs and nature.

This experience contributed tremendously to my understanding of traditional agrarian peoples and religions, the challenges of development, and the precarious survival of a way of life and cultures in post-colonial Africa. It introduced me to real-world sustainable survival where agriculture and living harmoniously with the life cycles of nature coexist.

Initiation – Finding Where I Fit in the Village

“Your beard is bad,” the wizened old chief said. “Why is it bad?” I asked. “Beards are for old men,” he replied, “and you are not old.” “In my country the young men have beards, and the old men do not,” I said. This was the end of the 1960’s and of course beards on young people were a cultural and political statement. In the village, too, beards were cultural and political statements. Elder men wore beards indicating their esteemed position in life and their authority. (Read more >>)