The Global Village

The World-wide Web of the 60’s

What the internet must be for present day Peace Corps Volunteers, the shortwave radio and the small Phillips cassette player were for Bill and me. Of course these only provided a one-way information network where we could keep up with world events from different perspectives, and with the latest music.

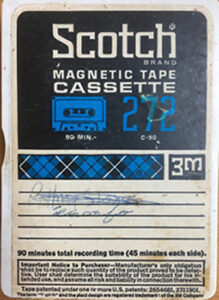

My cassette player was amazing new compact technology, only in its second year of widespread availability before I would leave in 1968. I was able to bring some cassettes with music, some pre-recorded, and some that I was able to copy off FM radio and our LP phonograph. It was my main “musical instrument” although I did have a little Hohner harmonica.

My cassette player was amazing new compact technology, only in its second year of widespread availability before I would leave in 1968. I was able to bring some cassettes with music, some pre-recorded, and some that I was able to copy off FM radio and our LP phonograph. It was my main “musical instrument” although I did have a little Hohner harmonica.

I had recorded a mixed bag of music: Some jazz, 60’s folk rock, some John Lee Hooker Mississippi Delta blues, and some Beatles.

Bill, on the other hand, had a twelve-string guitar and a wide repertoire of songs. He was a real blues man, and he had learned from deep roots on his ancestral family plantation where he would spend summers and hang out with sharecroppers and their children. He often spoke fondly of his best friend Joe Lewis and their adventures.

We connected during our Peace Corps training in St. Croix, Virgin Islands. Bill was an accomplished linguist, having studied abroad during his university career. When we were initially tested in French according to the Foreign Service Institute standards, he tested at a 5, native bilingual proficiency, while I tested at barely a 1, novice.

We experienced language immersion in the isolation of a tropical camp. The English dictionary was ceremoniously buried, and with it our permission to communicate in any English. We had language instructors from all over the francophone world, and especially from West Africa so we would benefit from their accent, way of speaking French, and cultural instruction. The animated, intense, staccato language drills gave no time for any of our English language habits to intervene.

Bill did not have to learn French, in fact he was given a couple of classes to teach, so he studied Dyula for about six hours a day. For the rest of us, in groups of four or five according to ability, our first language class was at 6 am, with a different instructor every hour, with the last class at 8 pm. With a ratio of about five trainees to each instructor, meals, recreation, technical, and cultural training were additional and specialized language training. At the end of three months we had to test at least at a 2.5, working proficiency, in French in order to go to our assignments in the Côte d’Ivoire. Since I got to that level after two months, they started me learning Dyula for two hours a day. (Dyula is a lingua franca of west Africa originating from Bambara in Mali.)

Although we were really tired each day we would need to unwind. Bill would play energetic blues and I would blow my harmonica while the others accompanied in various ways. He played John Lee Hooker’s songs and he sang with meaning …

I got a black cat bone

I got a mojo too

I got the Johnny Concheroo

I’m gonna mess with you

I’m gonna make you girls

Lead me by my hand

Then the world’ll know

The hoochie coochie man …

On Saturdays we had a day off but were admonished to speak French at all times (right!). Some would do laundry or go to either Christiansted or Frederiksted to shop, eat at a café and swim. Early on Bill and I hitchhiked from our camp to Christiansted. We met some young people and hung out. When they found out that Bill was a musician, they arranged for him to play in a club the following week. Towards the end of November the Beatles White Album was available and one of our new acquaintances got the tapes for us.

At the end of our training we were given our assignments and our living and working teams. We were all assigned in pairs to new, developing sous-préfectures in outlying areas in the northern Côte d’Ivoire. Each site was quite isolated and in some measure in the midst of building a new section of the village to house functionaries who would come to work and live in the new seat of government, and provide services to the areas. Bill and I were happy to be assigned together, since we had already begun to forge a friendship.

We discovered once we had lived in the bush for a while that the markets were their version of what we call the World Wide Web. The market system served the pre-technological, pre-literate community as a network of communication. Oral communication is a dependable way of getting a message to someone in another village or even in another region or country when passed through travelling merchants. More than once we would arrive in a distant village and the people we met knew that we were living and working in Sirasso. We had also developed connections, amongst the merchants and African café owners in Korhogo where we went for supplies, and we learned how news could travel.

The short wave radio also opened the world. Our Sunday ritual included afternoon listening to Radio Nederland Wereldomroep, the Dutch short wave network that played all the latest music. We listened to the Voice of America, BBC, French, Soviet, Chinese, and some pirate radio ships in the North Sea, all broadcasting to West Africa in multiple languages, even the ominous “special English.” To hear breaking news in special English was like witnessing crises unfold in slow motion. Especially chilling was the BBC signing off with “This is the end of the news.”

My language learning continued not only by immersion each day having to use them, but Bill’s proficiency in both French and Dyula were a bonus. In our multilingual universe Bill and I developed our own language, sometimes combining English, African French and Dyula in one sentence. We spontaneously used whatever words came to mind, even phrases from popular songs littered our conversations!

Walk on the Moon

It is so amazing to see signs of a different world entering a community that had virtually been unchanged for so long. Obviously motor vehicles had become a part of their reality. Bicycles and some manufactured goods started to change their life. Piles of surplus second-hand clothing from the U.S.A. found its way into rural markets. We got used to seeing a young man in a loincloth going out to the fields sporting a bowling shirt printed with the name of some Midwest bowling lanes, and monogrammed with the name of some guy! Perhaps we were as out of place as a bowling shirt in a bush village! (Read more >>)